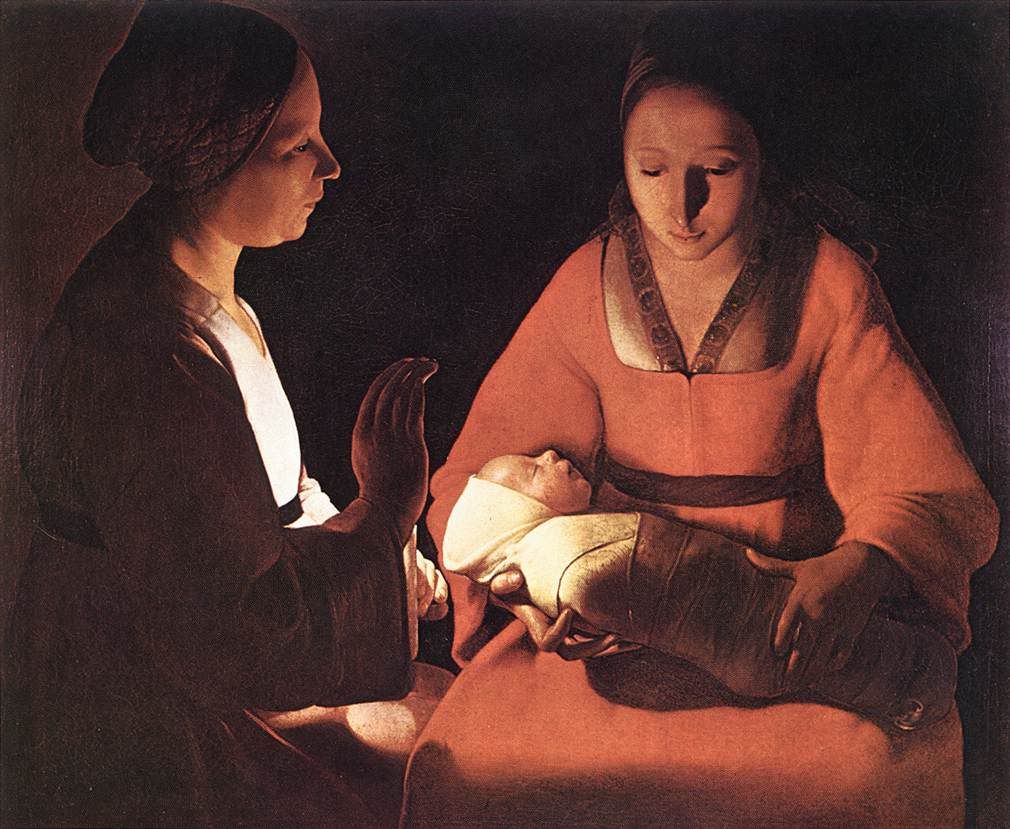

Georges de la Tour, 1593-1648, oil on canvas, 76X91cm., Musee des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, FR

The New-born Child, c. 1648

This glowing painting of a new-born child peacefully lying on the lap of his mother, receiving the adoring and wonder-filled attention of his mother and another woman, perhaps a member of the wider family circle, perhaps the midwife, draws us into the scene with its simplicity and immediacy. This could be a painting of any newborn at almost any time. The dress of the women places the painting in the seventeenth-century, but the wonder and rapt attention of the women could be drawn for any time or place in human history. Would that every child received such an adoring welcome to life!

Equally clearly, however, this painting marks a particular birth. Notice, the baby is “wrapped in swaddling clothes.” And La Tour’s use of darkness and light are also indicative that this is The Baby. Enveloped in darkness, the darkness has not overcome this birth and this child. Look again at the painting: What is the source of the light in the painting? Does the second woman hold a candle, focusing the light with her hand? Or is the child the source of the light? Certainly this brightness does not discomfort the new-born, does not startle the little one. This is the light-child, impressively ordinary and real, but glowing gloriously, the center of attention of the women.

Two revolutions made this painting possible, one technological and the other spiritual. Until the fifteenth-century it was impossible to represent the kind of incorporeal light that pierces through the darkness. Gold-leaf was often used, for example, in images of the Virgin and the saints to indicate the glow of light, but with less than satisfactory effect. But oil painting developed in the 15th Century, and these slow drying translucent paints could reveal form gradually emerging from shadow, and indicate the source of brightness. La Tour uses this relatively new capability here to striking effect.

The spiritual revolution, the Franciscan revival, was perhaps even more significant. In the High Middle Ages the central image associated with Advent and Christmas was the Annunciation, the announcement of God’s intent to send his Messiah into the world through the Virgin Mary. And the Mary of these paintings is clearly not a lowly peasant girl. She is the Queen of Heaven. Her literally golden halo announces her exalted state to us. And often her flowing robes are a very special royal blue, painted with a pigment made of ground lapis lazuli, a pigment costlier than gold and brought to Europe with great difficulty and at great expense from Afghanistan. Nothing, of course, could be further from the Mary of the Gospels, the wife ultimately of a peasant carpenter who could only afford the offering of the poor for the presentation of the child in the Temple.

To Francis and the Franciscans we owe the restoration of evangelical simplicity. Francis, the son of wealth and influence, intentionally turned his back on that wealth is response to the call of Christ and embarked on a life of association with and mission to the poor. It was Francis himself who “invented” the Christmas crèche, the tradition of focusing on the newborn baby, surrounded by his mother and Joseph and cattle in the stable of Bethlehem. That the God of all creation should make himself small for us is, of course, the Christmas Gospel. The baby in the feedbox of an ass in Bethlehem in all his helplessness and dependency was truly God and truly man, and in this way the God of the father has drawn near to rescue us from the darkness. La Tour so simply and beautifully captures this moment of “Sovereign Helplessness,” this wonder of grace, this invasion of the darkness by the Light of the World.

That our God has purposed to accomplish his mightiest works through means despised by the worldly wise ought to be a source of wonder and comfort and joy to His people. May this Christmastide, be such a season for you and yours.

Và đây là new-born Bảo Bảo: